Part One – Writing, Memory, Grief: Processing Gallipoli

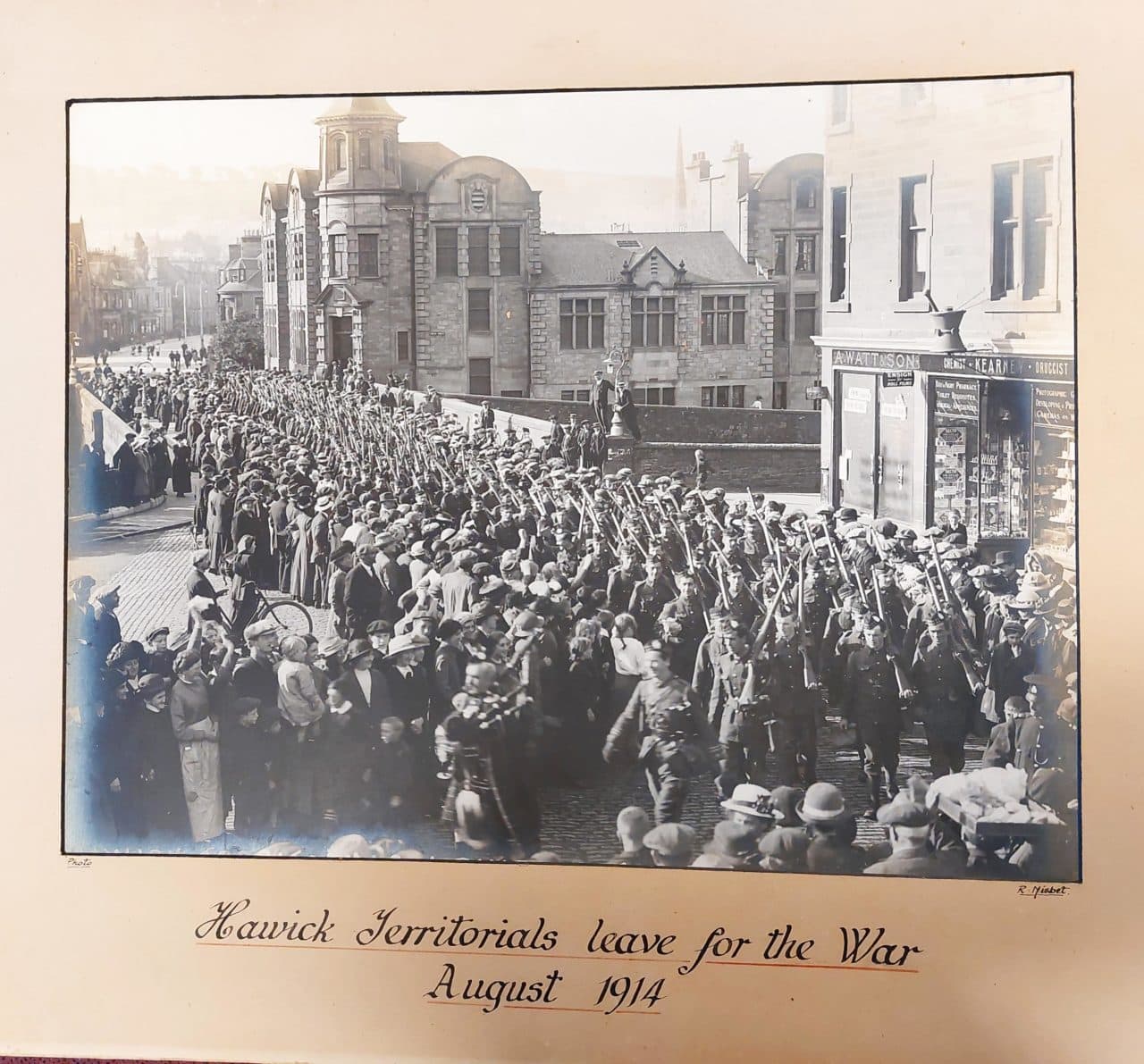

An archive photograph of the Hawick Territorials in August 1914. They march off to join the rest of 4th Battalion KOSB and what would become part of the 29th Division. A piper leads them, they have smiles on their faces and, although it is a still image, the enthusiasm of their march is evident. The road is lined by the friends and family there to send them off; waving hands, excited children, a few people climbing up the sides of streetlamps to get a better view. An occasional handkerchief is being used but this feels like more of a token nod to the group of men who will be missed for what was expected to be a short period of fighting. There is no sense of the horror and devastation of what was to follow and no one would have predicted that very few of these men would ever return.

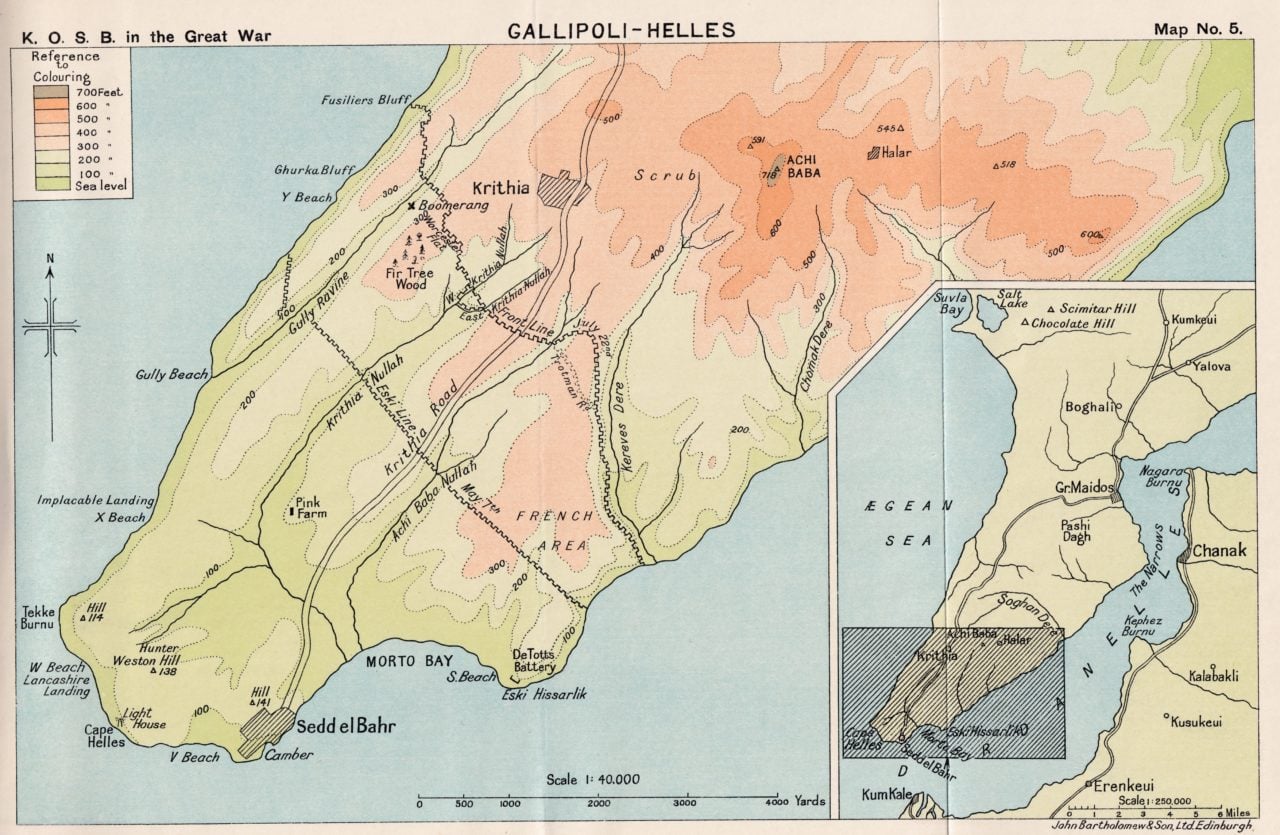

The Gallipoli campaign stretched from 19th February 1915 to 9th January 1916, with KOSB involvement from the start and having three battalions there – 1st, 4th and 5th. The 4th Battalion was part of the 52nd (Lowland) Division, the 1st Battalion was part of the 29th Division. The regiment’s time in Gallipoli was marred by challenging weather conditions which went from swelteringly hot to wet and freezing. The constant presence of flies, the diseases that came with them, the stench of putrefying corpses and maggots, and the increasingly ravaged surrounding landscape.

At the KOSB museum, the archive material and museum collection relating to Gallipoli is relatively extensive, ranging from detailed diaries to personal relics. After looking through these deeply personal words and items, it feels like a window has been opened into the lives and emotions of the men who experienced it first-hand.

The diaries of Captain Alex MacIntosh Shaw, 1st Battalion KOSB, give a detailed glimpse of the horrendous conditions at Gallipoli in 1915. The confidence of the British Empire leading to the reality of mass loss of life and huge scale warfare; a disastrous campaign. The start of his diary is fairly light in tone, describing the weather and scenery. There’s a sudden and very obvious change in atmosphere, shown in the following extracts. Shaw hints at the scale of death he is witnessing and the fragility of life. Wearing colours that camouflage and helmets shaped to deflect shrapnel, he compares the soldiers to ants – they have become subterranean and vulnerable.

We have invoked terrible jinn. Where indeed are the terrible bolts of Jove compared to the “Heavies”? Man seems such a frail creature in the presence of these devastating monsters. A creature slim and pink with so thin an eggshell of natural protection for his brains – a mere white ant running in and out of holes and runways in the earth.

He then flits between images of lavender and wood peckers to bad dreams and exhuming the body of a young soldier. He might say he is keeping cheerful but it sounds like a nightmare.

Mail came. Some sweet lavender, very home-like. Saw a dappled wood pecker last night just like the Chinese variety: it reminds me of the Pae Ma Ch’ang. This war is like a bad dream. I feel very dirty but keep cheerful and full of hope. Identity disk of one of my company was sent in. Some Territorials had buried him last night near our well. They said he had no wound so the Dr and I went down and had him exhumed. He was shot through the heart. How like sleep death is. I felt I was tucking the poor lad into bed in his shallow grave.

This makes me consider the purpose of the diary. Is he simply cataloguing his experiences? Recording the day to day? Or is he using his diary as a way of dealing with the trauma of Gallipoli? A way of processing the unimaginable through the familiar pen and paper? In a time of fear and uncertainty, the ink on the page gives permanence and validation. Shaw’s diary is detailed and extensive, an unparalleled account of KOSB experience at Gallipoli. Through it, we see everything from the unscalable dusty hillsides, the flies, disease and maggots, to the occasional reminders of beauty and the constant threat of death.

In 2023 I was cataloguing the museum collection and, over the course of a few weeks, began to find objects that I knew were not only related by place and time, but came from the same person. Captain Robert Robertson Morrison Lumgair was a fairly well known cricketer along the Borders who found himself at Gallipoli, later killed in action on 19th April 1917. Archive material includes his diaries but these are mainly filled with functional notes on training; a recording of his experiences to a certain extent, but not his emotions. What stood out to me was a belt, meticulously decorated with buttons, collar badges and shoulder titles belonging to the soldiers of different regiments he had encountered as part of his Gallipoli experience.

The belt records the names and insignia of people he has encountered, people who more than likely did not survive the experience, making them mementos of people, memento mori of those no longer alive. They were there together, some were wounded, some died and few survived, but the memory of them on this belt records their existence.

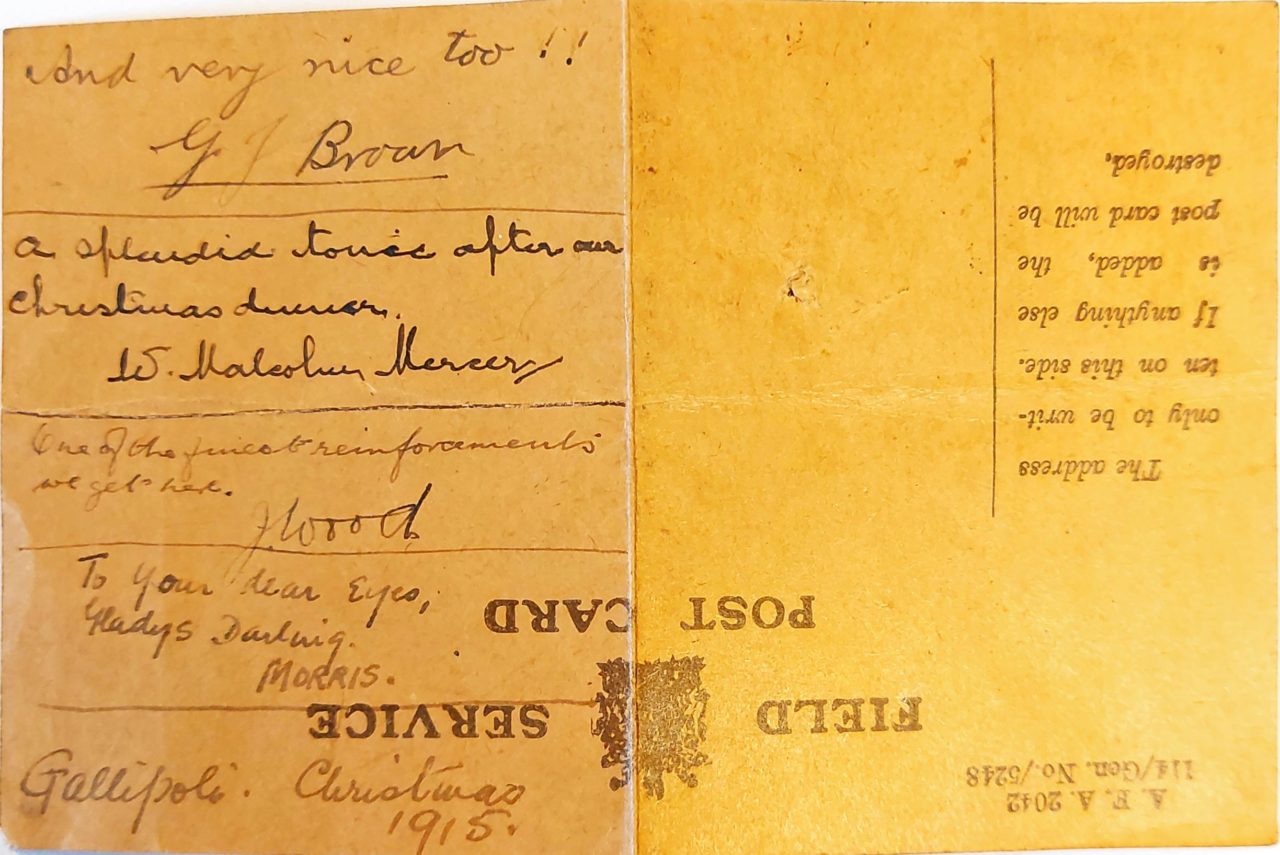

For Christmas 1915, Captain Lumgair sends a card to his wife, Gladys, signed by him and by other men in the regiment.

‘To your dear eyes, Gladys Darling, Morris’ is so simple but so intimate. So many young men rushed to join at the start of the war, eager to be involved before it was all over by Christmas, but they write here, upside down on a field postcard, with the meaningful date of ‘Christmas 1915’ and the war is very far from being over. At a time like this, it seems that family becomes simultaneously more fragile and more firmly bonded.

Months later and focusing on a completely different part of the museum collection, I found a silver cup, the Lumgair Cup, created in memory of Captain Lumgair by his wife.

The Lumgair Challenge cup acknowledged the sporting prowess of Lumgair himself and also the achievements of his regiment after his death. Another record of his life and memento of his death, an act of remembrance by his wife.

Looking at the photograph of Hawick in August 1914, it is hard to believe that many of those soldiers will have so soon experienced the horrors of what happened at Gallipoli. The huge loss of life is evident on the Halles Memorial and on memorials in towns along the Borders and beyond. The events, dates and details of the Gallipoli Campaign are recorded in history and are widely available to all who are interested. The first hand and more intimate experiences are available also but, quite appropriately, more discretely hidden. These recordings, in whatever form they take, show how people have dealt with trauma and turn acts of recording into acts of remembering and, ultimately, into acts of remembrance.